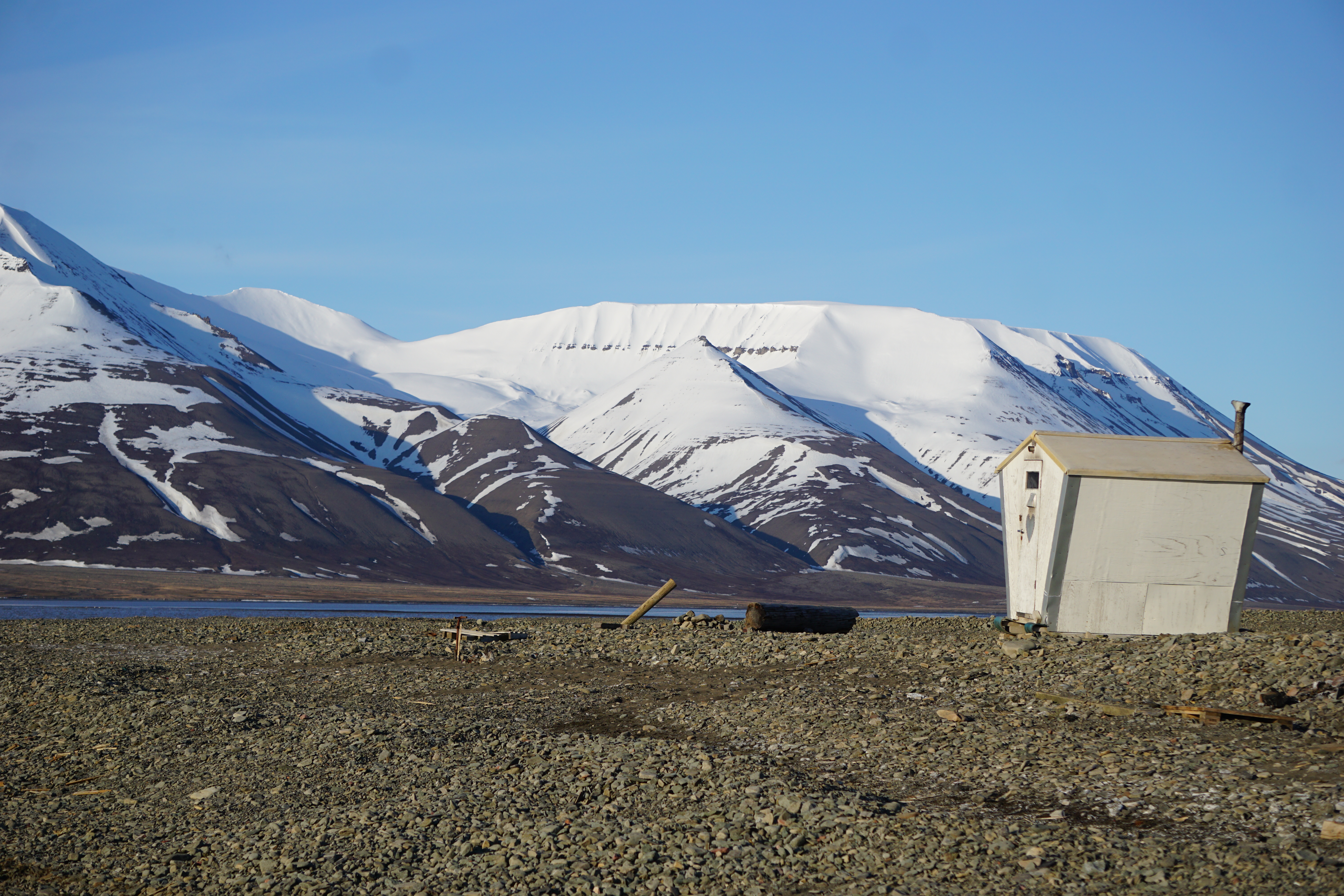

This fieldwork campaign on Svalbard in the summer of 2023 was perhaps my most significant Arctic research trip so far. It was not only my longest fieldwork to date (2 full months), that included a new personal “furthest north” record, but also the first trip I had gotten funded and planned entirely independently. And perhaps most importantly, it felt like a final reckoning with setbacks and personal challenges I had had to deal with in the years leading up to it.

In June, the tundra was still emerging from under the snow and we experienced some last snowfall in Longyearbyen. Long days out in the field during which we were sitting still to count tiny emerging leaf shoots and read out sensors were beautiful but also a challenge. We needed every single layer of clothing we had brought.

By late June much of the snow had disappeared from the valleys. Our research sites were snow free and our fieldwork was in full operation. Due to high snow accumulation in spring and hence late snowmelt, many areas were very wet or flooded. Mysterious misty days alternated with periods of bright sun and (for Svalbard) very high temperatures. Some days we were wondering how much sense it still made to carry forth our experiment, which consisted of supplying extra water to simulate heavy rainfall, in plots that were already so wet. Other days we took off and enjoyed hikes and a boat cruise.

By July the mountaintops became less and less white, and our shadows became noticeably taller on late nights. Still, it would still be many weeks before the sun would set for the first time again. Fieldwork data was trickling in, and I found time to go on a small cabin trip to Bjorndalen.

I spent a beautiful week in Ny-Alesund shortly before returning home. Although I missed the darkness at night, the trees and many people back at home, it was still very hard to leave this beautiful archipelago on the very last day of July. It is starting to feel like a new home.

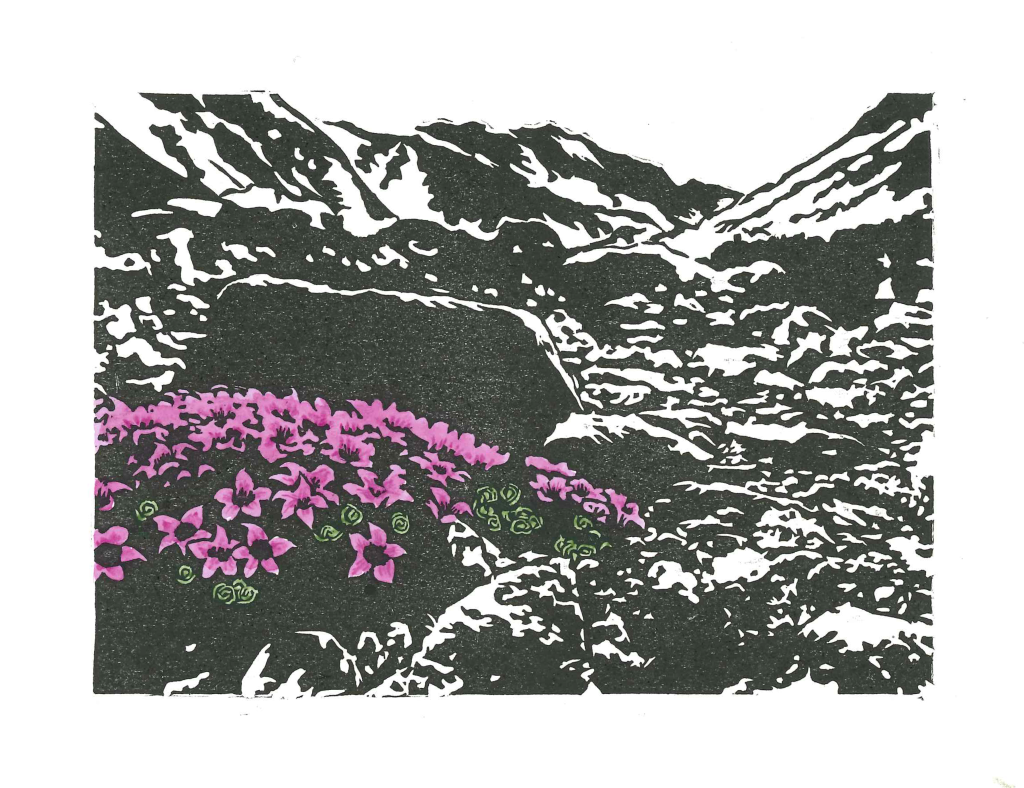

A walk in Endalen and food and drinks with friends filled my final weekend on Svalbard. It was rainy and cloudy all day in Longyearbyen and Adventdalen, but somehow Endalen had some mysterious spots of sunlight shining through. Can you imagine how hard it was to leave Svalbard with amazing scenes like this..?

Leave a comment